It began the morning after I clicked publish.

A twisting deep under my ribs, a sudden surge of pain so sharp it made me bend in half. The ultrasound and blood tests that followed turned up nothing, but I knew what it was. Not a gallbladder flare or random spasm, but something older, something energetic. A revolt in the solar plexus, that golden center just below the heart, the body’s chamber of personal power.

After nearly a year of silence, I had finally written again. Within twenty-four hours of pressing post, my gut locked down like a vault. I’d written about belonging and bravery, about feminine voice and visibility, and my own body had answered with a clear message: You’re not safe.

It wasn’t the first time I’d felt it. A lifetime of standing slightly behind my words. Shrinking a little before the light could find me. Maybe it’s ancestral, a lineage of women who learned that being seen can hurt. Whatever its origin, the pain was real, and I needed a guide to understand it.

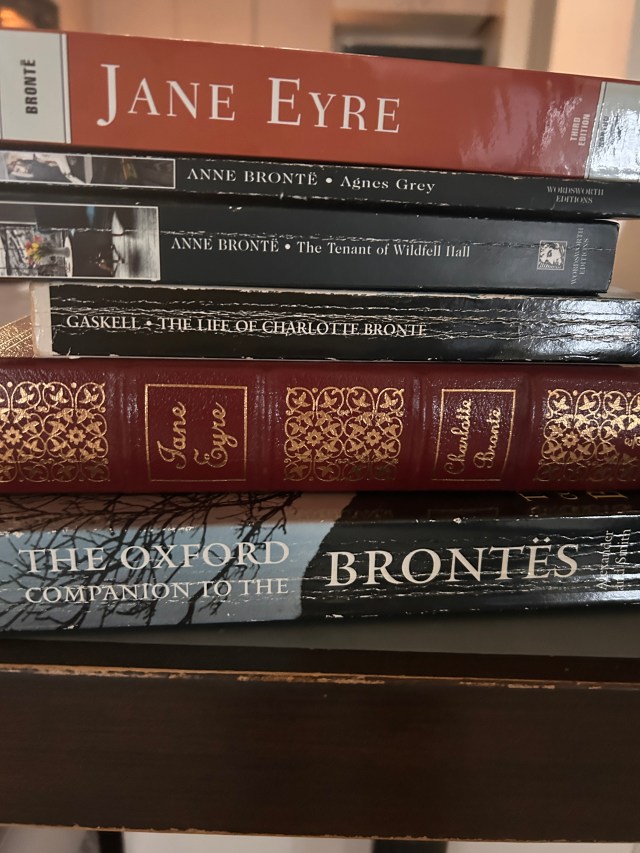

When my body breaks, I turn to books. And when I want truth, I turn to women who wrote it despite the fear.

This time, I called on the Brontë sisters, those fierce, wind-bitten voices from the Yorkshire moors who knew what it was to hide behind masks. Charlotte, Emily, and Anne: three women publishing under the names Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. Their era taught them that a woman who published risked being called unwomanly, even obscene. Yet they wrote anyway. Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, Agnes Grey, all in 1847, the same year they hid behind male pseudonyms. When the world demanded proof, they stepped forward, revealing themselves to be the authors the Victorians adored and condemned in equal measure.

I wanted that courage. That lion-hearted steadiness. That sun-bursting center that doesn’t collapse under scrutiny.

So I returned to the memory of my own pilgrimage to Haworth, the village where the Brontës lived and wrote. I had gone there seeking something intangible, a map back to my core.

The Ascent

The day I arrived felt apocalyptic. Rain came sideways, and wind howled like an old wound. The cobblestones darkened to pewter gray, and my umbrella turned inside out before I even reached the crest of Main Street. The Parsonage stood at the top of the hill, square and defiant, its windows like watchful eyes facing the storm.

Every step up that hill felt like an initiation. The air smelled of peat and chimney smoke, of wet wool and stubbornness. This was no place for fragile constitutions. As I climbed, I thought of the Brontë girls trudging these same stones, their skirts dragging through puddles, their imaginations burning brighter than the the town’s lamps.

By the time I reached the doorway, the wind had quieted, as though testing whether I’d earned entry.

The Hallway of Loss

Inside, the hush was immediate. The air held a faint scent of varnish and vellum, as if every surface had absorbed the years. Near the front hall hung a simple sign:

Maria Branwell Brontë, the sisters’ mother, died on this day, September 15, 1821.

I paused at the date, taken by its quiet symmetry. It was the exact date of my visit, September 15th, more than two centuries later.

Grief marked this house from its foundation. Charlotte was five when their mother died, Emily three, Anne one. Two older sisters perished not long after, claimed by tuberculosis. The family learned early what it meant to live beside death.

“The loss of their mother,” Elizabeth Gaskell later wrote, “was the first great sorrow that came to the little household, and it sank deep. The children … never forgot it.”

I thought of my own losses, the way death rearranges the furniture of the heart. When my mother died, I sobbed from a place deep in my core—a primal kind of howl that frightened me. It came from the same hollow I sometimes feel ache beneath my ribs, as if grief and voice were housed in the same chamber.

For a moment, the room seemed to breathe with me. Each creak of the floorboards whispered: Keep going.

The Study: Permission

Reverend Patrick Brontë’s study was spare but orderly. A desk, spectacles, the presence of a father who valued thought as much as faith. He couldn’t see well but he saw the potential in his children, teaching them at home and urging them to “read and think for themselves.” In this small room, that permission still hummed in the air, a belief that the mind was holy ground.

Charlotte carried that conviction into her own life, later writing, “I’m just going to write because I cannot help it.”

Standing there, I admired her. Somewhere within me, a younger self still waited for that same freedom, to speak without apology, to create without asking. I wasn’t always that way. Before schools and rules, I was a wild child with tangled hair, dirty fingernails, and a voice too loud for small rooms. Each time I was told to be still and quiet, something in my belly contracted. I felt a faint echo of it now. The body remembering its old defense even as it tried to let go.

The Dining Room: Communion

The dining room was smaller than I expected. The mahogany table bore its quiet scars; ink stains and burn marks softened by time. Shelves of worn spines lined the walls, a parliament of books watching from their place above the hearth. Here, the sisters walked in circles reading aloud their drafts, trading pages, arguing, laughing, rewriting into the night. I imagined the rhythm of their footsteps, the heartbeat of creative sisterhood. Confidence multiplied by companionship.

I thought of my own writing circles, the rare joy of being met and mirrored by kindred minds, of ideas made braver by witness. Yet there’s always a catch. When praise comes, something in me contracts. The Brontës must have felt it too.

The Era, a London newspaper, called Jane Eyre “a work of irresistible freshness.”

Graham’s Lady’s Magazine described Wuthering Heights as “a strange sort of book…impossible to begin and not finish.”

Praise and alarm intertwined, as though the world admired their fire but feared its heat. I knew that tension. The longing to be seen. The instinct to shrink back. As I heard the rain drumming the panes like applause, I felt that same tug between exposure and retreat.

The Bedrooms: Courage and Faith

Upstairs, the walls seemed to draw closer. Emily and Anne shared a simple room, yet it was charged with ideas. I imagined Emily on one side, Anne on the other, two temperaments sharing a single breath of heathered wind.

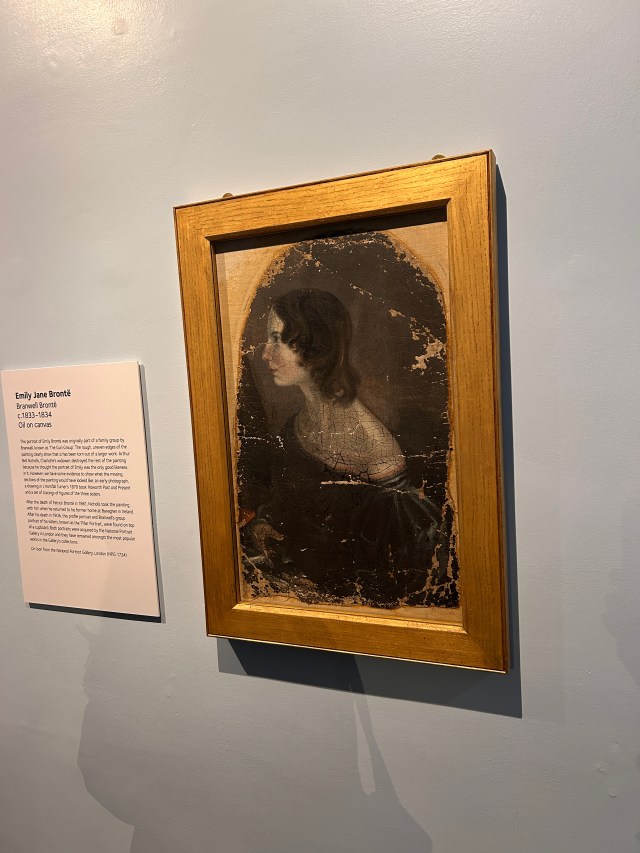

Near Emily’s corner, the wallpaper lifted slightly where damp had seeped in, and a low tremor passed through the glass each time a gust struck. I pictured her pages scattered in a windswept swirl. Deemed strange by the world, she wrote Wuthering Heights with a fiery frenzy, fueled by the wildness within.

When Charlotte published her poems without asking, Emily raged. To her, exposure felt like betrayal, the rupture of something sacred and private. I understood that too. Sometimes the betrayer isn’t another at all, but the self that rushes to be seen before it feels safe. Yet from that fear and fury came her gothic masterpiece. Through Catherine’s cry across the moors, Emily’s own voice breaks through: “I wish I were a girl again, half savage and hardy, and free.” A feral longing, a cry from the gut, not weakness but the body remembering its power.

Anne’s half of the room was quieter, the order almost tender. A cross hung on the wall, a prayer book open to a psalm about endurance. Even the light seemed softened, catching in the folds of a linen cloth. “I desired to be useful, to be kind,” she had written in Agnes Grey. Her power was restraint, her strength devotional.

Between those two halves of the room, I stood suspended between storm and prayer, instinct and grace. One side of me desperate to roar, the other learning how faith itself can be a kind of fire.

The Brother’s Room: The Shadow

Then came Branwell’s room: sketches, ink stains, empty bottles, a chaos of unraveled promise. The air was heavier here. The brother who had once written alongside them had drowned in failure and self-loathing.

On the wall hung the portrait he had painted of his sisters. He had first placed himself among them, then painted his own figure out, leaving behind a pale column of light. It was as if he’d already begun to erase himself, unable to hold the weight as the only male heir. Perhaps he feared exposure too, the rawness of being seen before he’d steadied his own flame. He eventually drank himself into annihilation, trying to fill the hollow that no amount of brilliance or brandy could ever soothe.

I thought of all the ways power can distort when it’s not grounded: ambition without compassion, talent without humility, exposure without inner steadiness. My gut clenched slightly, a reminder of how thin the line can be between creation and destruction.

The Churchyard: Impermanence

Outside, the storm had quieted. I wandered through the adjoining cemetery where lichen-covered stones leaned like weary sentinels. Over forty thousand souls rested there, consumed by the damp earth that had also nurtured the Brontës’ imagination. Beneath the church lay the family crypt: father, mother, children, all but Anne, who rests by the sea.

I knelt to read a fading inscription, the letters eroded by weather and years. The ground pulsed faintly under my hand, the way the body sometimes does when it’s ready to let go. Maybe pain is simply the reminder that time is brief and creation urgent.

Jane Eyre’s words rose up from the ground like a benediction, “I am no bird; and no net ensnares me.”

I whispered a small prayer to the sisters who had dared to write, to every woman who had swallowed her voice to survive.

The Return: Release

Back home, my body still ached, but it felt different. Less like a wound, more like a current.

I thought about digestion. How every act of creation asks the body to process something immense, to take experience in, break it down, and transform it into sustenance. Perhaps my solar plexus wasn’t punishing me for writing. Perhaps it was reorganizing, learning to metabolize its own radiance.

I pressed a hand to my stomach and thought of Charlotte’s courage, Emily’s wildness, Anne’s grace. Alive in the quiet rhythm beneath my palm.

Quotes

“The Brontës teach us that the fiercest storms can live inside the smallest rooms.” — Graham Watson, The Invention of Charlotte Brontë (2025)

“They wrote as if creation were a moral duty — to speak was to live.” — Elizabeth Gaskell, The Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857)

Further Reading

Gaskell, Elizabeth. The Life of Charlotte Brontë. Smith, Elder & Co., 1857.

Lutz, Deborah. The Brontë Cabinet: Three Lives in Nine Objects. W. W. Norton & Company, 2015.

Watson, Graham. The Invention of Charlotte Brontë: A New Life. Pegasus Books, 2025.

What fierce honesty, Julie. It’s beautiful! It reminds me of Hemingway: ‘All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.’Keep writing your truth!

LikeLike