Miss Austen’s merits have long been established beyond question; she is, emphatically, the novelist of home.

– Richard Bentley, 1833

I stared at the home across the street, longing to go inside.

Not even the clinking china and low hum of English voices could distract me from the house beyond the hedgerow. Through the Tudor teahouse window, Jane Austen’s House in Chawton, Hampshire waited – red brick, white trim, and the quiet promise of belonging. I had come all this way to see where she had written herself back into home. Yet as I sipped the English breakfast, a hollowness lingered, a hunger that milky tea and jammed-up scone could not fill.

For weeks I had told friends I was visiting Jane Austen’s House Museum. But that was not quite true. What I wanted was harder to name, a place that might show me what home means after so many years of searching for it without success.

I want to go home.

It is a phrase I have whispered all my life, in airports, in apartments, even in rooms I once thought were mine. After twenty-five moves, I still rent a one-bedroom apartment – a life in motion, always half packed. The Welsh have a word for this ache, hiraeth, a longing for a home that no longer exists, or perhaps never did.

Maybe it began the day I was lost in Seville at four years old, a tiny, teary girl threading through blaring traffic trying to find her way back home. Or maybe it began later, in adolescence, when I asked friends to drop me off down the road, so they would not see our weathered New Hampshire barn house, its paint peeling and pigs reeking in the heat. Perhaps the longing deepened when my mother died five years ago, and siblings talked of selling her Florida home. Wherever it began, an invisible threshold seemed to stand between me and belonging itself, between me and that quiet sense of safety and wholeness.

So here I was, sitting across from the home of a woman who understood the peril and poetry of that word, home. Jane Austen’s heroines were always one page turn away from losing theirs: the Dashwoods exiled from Norland, the Bennet sisters marrying to keep a roof, Anne Elliot estranged within her own walls. Jane herself had moved from Steventon to Bath to Chawton, her life shaped by displacement.

And yet she made art from the ruins.

I wanted to stand in the rooms where she rebuilt her life, to touch the small table where she wrote Pride and Prejudice, to walk her garden paths, and to ask quietly what she had learned about finding a home.

I paid my bill, crossed the narrow lane, and stared at the facade. The cottage seemed to stare back, reading me as much as I was reading her. After her father died, Jane, Cassandra, and their mother were essentially homeless, drifting from place to place for four years. It was Jane’s wealthy brother, Edward Austen Knight, who offered them this house, once occupied by his bailiff. The front rooms would have been noisy, set along the main coach road, but still Jane found peace here. In an 1809 poem, she wrote:

Our Chawton home, how much we find

Already in it to our mind;

And how convinced that when complete

It will all other houses beat.

I entered through the side gate, hoping to understand what made this house beat out all others. In the back courtyard, cotton dresses hung to dry on a clothesline, and the scent of chamomile and rosemary drifted from the herb garden. A small donkey cart waited near the hedge, as if ready for errands or visits. Inside the old bakehouse was a costume room where I tried on empire-waist gowns and ribbony bonnets, a chance to become Emma Woodhouse back from a ball.

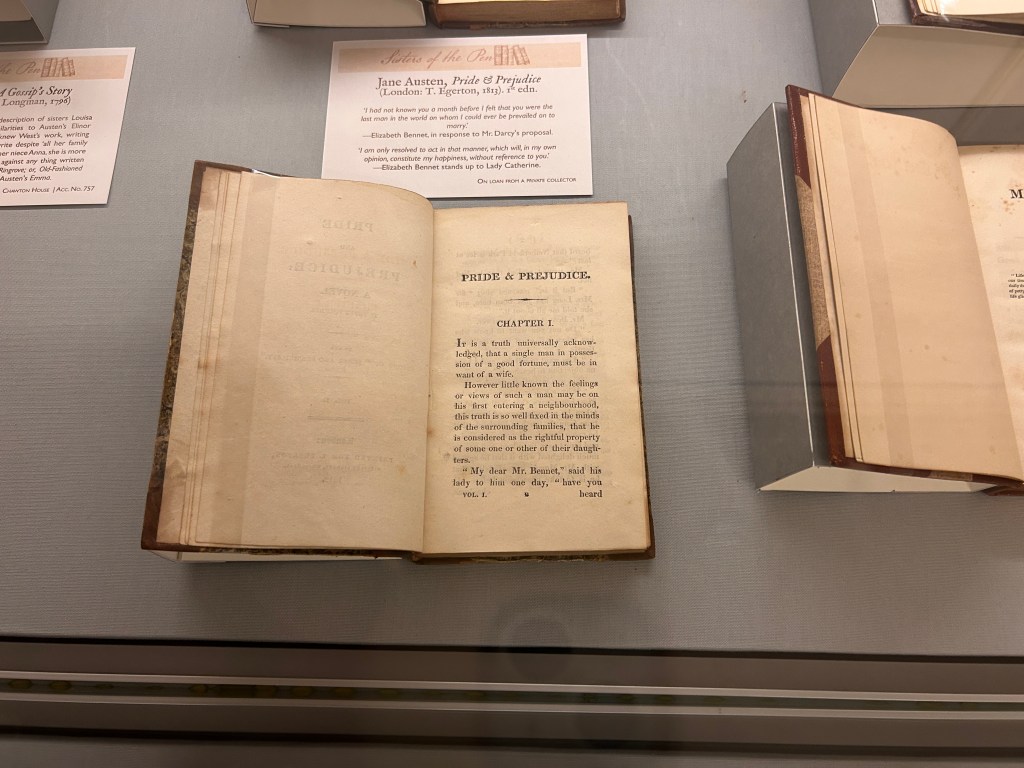

I crossed the threshold of the back door as if I were stepping into one of her novels. Creaky floorboards served as a spine, faded wallpaper as its pages, each corner whispering a story. In the drawing room, I ducked beneath a low beam, aware of the generations who had done the same. Original letters, first editions, and inked drafts lined the walls. I imagined evenings when Jane sat near the piano, reading new chapters to Cassandra while their mother stitched nearby, candlelight pooling across the table.

Then I saw it: Jane’s writing desk. The twelve-sided walnut table was scarcely larger than a dinner plate, yet here she revised or wrote all six of her novels during the eight years she lived at Chawton. I leaned over the glass case, studying the letter laid across it, wishing it might reveal what made this house her sanctuary. For the first time in years, she had space – no husband, few chores, no need to move again. Though she loved wit and lively conversation, her deepest contentment, I suspect, was in solitude, where the rhythm of her sentences became a kind of prayer. I could almost see her inky fingers and hear the soft scratch of her quill, the shuffle of paper, the pulse of thought finding shape.

In that moment, she appeared to me as a kindred spirit. I too have known that still, bright current that flows through writing, the one that connects me to myself and to something beyond. I felt it most vividly the time I wrote about my mother dying; in those moments, the act felt whole and holy. Perhaps that spark is the closest I have come to home, something not tied to walls or furniture, but to the quiet aliveness that stirs inside me, reminding me that belonging begins within.

The rest of the house was practical but plain: a dining room, a kitchen, three small bedrooms upstairs. These were rooms for living, not for transcendence. Jane’s presence seemed to dissolve beyond the writing desk. I knew I needed to go further, to see the other Chawton home, the grand manor where her brother Edward lived with his family, a quarter mile down the lane.

The long driveway leading to Chawton House was lined with chestnut trees and open fields, a landscape wide enough to hold the Austen family’s many branches. The brick and stone mansion loomed ahead – the kind of place my adolescent self would have begged to be dropped off, if only to pretend she belonged there. Jane had come here often for Sunday dinners and Christmas gatherings. Her mother and sister lay buried at the small church on the grounds. It was an impressive place to rest, but I wondered what it meant to live here.

Stepping through the arched doorway of the three-story Elizabethan house, its formality rose around me. Portraits stared from every wall, faces lacquered in gold and burgundy, the air scented with wax and polish. The aged oak paneling made my footsteps echo with intimidating self-consciousness. This was not the kind of home that easily welcomed a woman without wealth. I tried to imagine Jane here, both included and excluded, visiting her brother’s prosperity like a guest in her own family story.

When I asked the guide about the family, his face lit with affection. He was a gentle man with silver curls, speaking as though the past were an old friend.

“Edward Austen Knight was Jane’s older brother,” he began. “He was adopted by Thomas and Catherine Knight of Godmersham Park. They had no children, so they raised him here in this house.”

I nodded, taking notes, until he added, almost under his breath, “I used to play with my cousins in this room.”

I looked up. “Wait, what? You lived here?”

He turned his name tag toward me, smiling. Jeremy Knight – Jane’s fourth great-nephew who had lived in this house for forty years.

The house suddenly felt warmer, as though its heartbeat had quickened. Here was a living Austen, not in oil paint or marble, but in flesh and voice.

“You’re like a celebrity!” I said.

He laughed. “Oh no. I’m not even on Facebook. I just volunteer here to keep myself out of trouble. My daughter’s the celebrity. Have you read her book?”

He was referring to Jane and Me: My Austen Heritage, written by Caroline Jane Knight, another keeper of memory and another soul shaped by place.

“She was heartbroken when we had to move.” His lip stiffened as he carried on. “We simply couldn’t afford to keep the house. You know, roofs, taxes, that sort of thing.”

The room fell quiet for a moment, as if both of us were listening for what remains when a home is gone.

My gaze drifted toward the diamond-paned window. I thought of losing my mother’s home – her oil paintings of oceans and lilies, her mugs still stained with coffee, her patio chair shaped by her warm body. Is letting go the truest way of keeping, allowing what once sheltered us to live on as memory, as story?

Jeremy’s smile tilted wryly. “So now it belongs to the Chawton House Library, a center for early women’s writing.”

I thought how perfect that a house once sustained by privilege now lived on as a sanctuary for women’s voices.

I wandered through the rest of the home, following narrow corridors to an exhibit called Sisters of the Pen, devoted to the women who preceded, influenced, and followed Jane. I imagined her leaning over the shoulder of a graduate student bent over a first edition of Mansfield Park. Somewhere down the hallway, her words seemed to stir again as a scholar turned the opening pages of Persuasion. She was alive throughout the house, in every sentence, in each reader who lingered over her lines.

Later, I found Jeremy again in the library. The air hummed with the sound of a dehumidifier. Curtains closed to protect the rows of books towering from floor to ceiling, each spine a quiet pulse of history.

“This was my father’s favorite room,” he said, motioning me closer. Then, with a conspiratorial grin, he pressed a shelf of faux books, and it swung open to reveal a hidden liquor cabinet.

I laughed aloud. “How old were you when you discovered that?”

He leaned in, cupping his hand to his mouth as if to reveal a secret. “I built it.”

Suddenly, Jeremy seemed like he was a book: his voice, his mischief, his care turning the house into something breathing and bright. The room seemed to exhale; what had felt like museum now stirred with warmth and memory. Through him, home revealed itself not as a possession but as an ongoing conversation between the living and the dead. Perhaps I didn’t need my mother’s physical home either. She too lived in my memories, my stories, my words.

When I stepped out into the gray afternoon, rain began to fall. I started down the lane toward Alton, my shoes sinking into the soft earth. Minutes later, a red Suzuki from another era slowed beside me. Jeremy leaned out the window.

“Where are you going?”

“Alton.”

He motioned his crinkled finger to hop in the car.

“You’re my real-life Mr. Darcy,” I teased, laughing as I climbed in.

As he dropped me in town, he waved and drove off, the car disappearing around the bend. I stood there a moment, the scent of rain rising from the road, sensing that perhaps I didn’t need to keep searching for my way home. I was already inside – in the aliveness of story, in the joy of connection, in the quiet pulse I started to recognize as my own.

Quotes to Write Home About

“Ah! There is nothing like staying at home for real comfort.” — Emma

· “There is nothing so like home as a little cottage.” — Letter, 1800

· “My idea of good company… is the company of clever, well-informed people who have a great deal of conversation.” — Persuasion

· “There are as many forms of love as there are moments in time.” — Personal letters (attributed)

· “One half of the world cannot understand the pleasures of the other.” — Emma

· “We are very snug, with little coteries, and our quiet comforts.” — Letter, 1813

Further Reading

Jane Austen’s House Curators. A Jane Austen Year. Rizzoli / Jane Austen’s House, 2025.

Wilson, Kim. At Home with Jane Austen. Abbeville Press, 2014.

Worsley, Lucy. Jane Austen at Home: A Biography. St. Martin’s Press, 2017.

I am so glad to be able to call Julie my niece. Julie the best writer ever and it is so good to be reminded of this. More from Julie💜JaneJane Cooper

LikeLike

Now I’m blushing 🙂

LikeLike

Julie, this is fantastic and as RR is getting at, the home is within. Like you, never quite feeling at home and what you are discovering is so helping me as well. Not to old to grow. Also, tried to sign up for your blog, but was stymied by creating an account. Can you sign me up. I do love your writing and your insights. Sending much love and you are always welcome here💜 PS When Gramma and Grandpa sold Eichybush, I did feel the lose of home and in some ways still do.Jane Cooper

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awww, thanks Jane! You are too kind, and I know I can always count on your place to welcome me home. I’ve thought about Richard Rohr’s take on home for a while now. It definitely fed these ideas here. And if you received an update in your inbox that I posted this, you’re all signed up! Thank you again!

LikeLike

Thanks Gin! The piece was actually a struggle. The writing wheels are rusty! But thanks for being my copilot and joining me in the story!

LikeLike